What Are Some Cultured Mastered the Art of Narrative Painting

El Greco: A mod creative person in the 16th Century

This year is the 400th anniversary of El Greco'southward decease but his works can feel shockingly modern. Jason Farago examines how his works influenced Manet, Cézanne, Picasso and Pollock.

F

Few artists stick out from the standard tale of western painting more pointedly than El Greco, the great outlier of the belatedly 16th Century. Deeply religious, passionately single-minded, he merged the art traditions of iii different countries and found his ain unsettling painterly language, i that took a very long time to observe its most receptive audience. Flip through the pages of a textbook or wander through the permanent drove of a major museum and you can sometimes fool yourself that art history is a clear and predictable progression, one style and one century inevitably giving way to the adjacent. But art history, we know, isn't nigh so simple, and El Greco, like few other painters, gives the great delight of seeing that story disrupted and contradicted.

El Greco and Modern Painting, a major exhibition at present on view at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, demonstrates the influence of the Spanish-Greek artist on figures as divergent as Manet and Picasso, Beckmann and Pollock. It too, inevitably, suggests that El Greco was in some sense 'mod' himself. Wrenched out of time, El Greco speaks more than easily to secular museumgoers than many religious artists of the 16th century. We can look at his altarpieces and his portraits as bold experiments with form and color, or see in his torqued figures the presentiment of brainchild. Nonetheless looking at El Greco's influence on modern artists offers a chance to see not only what is timeless in the artist'south work, but also what's non. And putting El Greco alongside the moderns tin can help us see art history as more than just a series of dots on a line, just a multi-directional conversation that upsets time itself.

For another age?

El Greco – or Domenikos Theotokopoulos, equally he was born – was born in 1541 in Crete, which was and then a colony of the Most Serene Republic of Venice, the reigning bosses of the Mediterranean. After grooming as an icon painter, he moved to Venice and afterward to Rome, yet despite the booming market for religious painting in the midst of the Counter-Reformation, El Greco'southward career took some time to get going. Information technology wasn't until the late 1570s, when he settled in Toledo, Spain, that the creative person began developing both the contacts that would sustain his career, too equally the groundbreaking, agonizing, unprecedented way that would characterise his mature art.

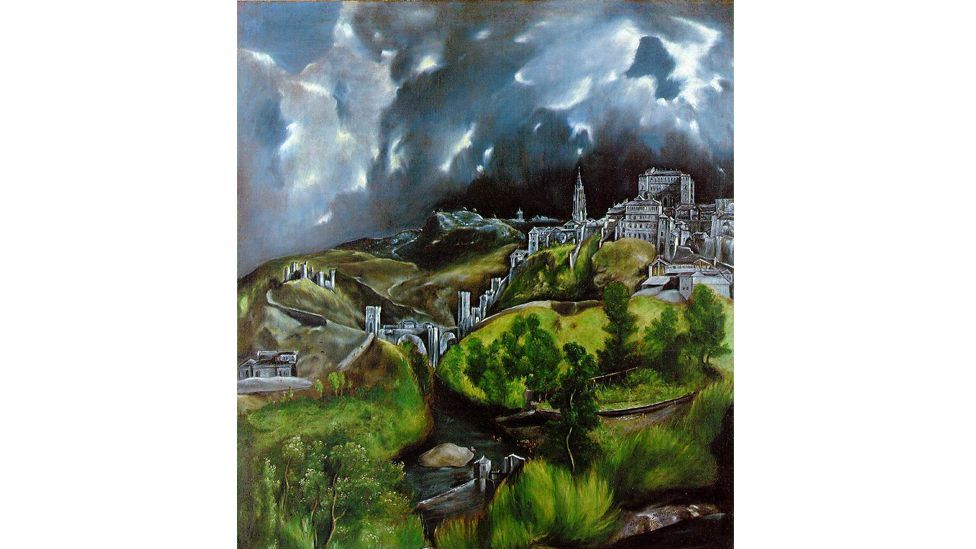

View of Toledo by El Greco (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

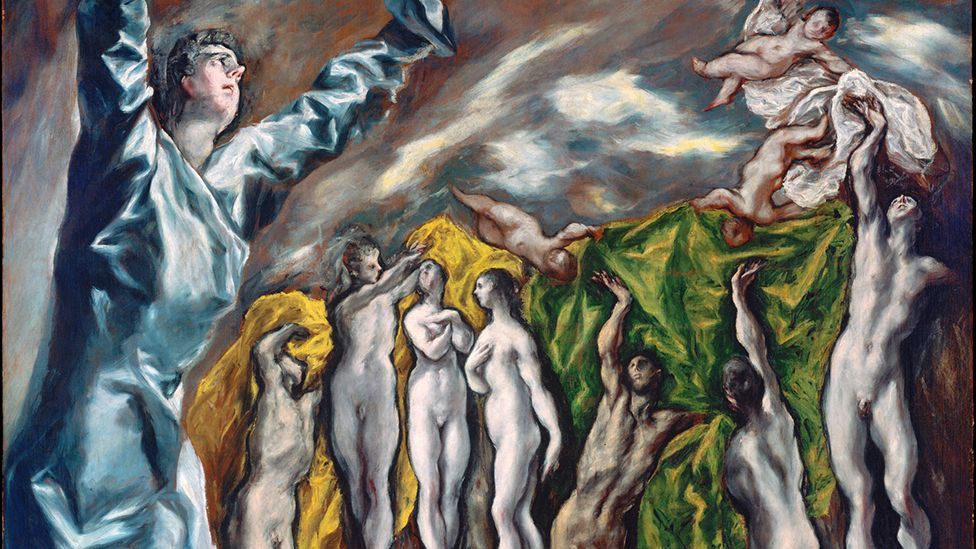

In Venice, the young El Greco produced equanimous, vibrant tableaux in the manner of Titian (whom he may have worked for at one point; the historical record isn't clear), and had he stayed at that place he might be remembered today equally a talented only not extraordinary painter of the belatedly Renaissance. Only in Spain his fine art became more penetrating, more Mannerist, and much more than idiosyncratic. Figures, especially faces, became elongated and corkscrewed, almost postal service-human. Striking, at times reckless apply of chiaroscuro makes pink and blue robes burst from the canvas. Rather than anatomical verisimilitude, El Greco's Spanish-period paintings strove for religious intensity and sensual potency, and he was happy to sacrifice naturalism to get at that place. Looking today at his creepy eschatological Vision of Saint John, from 1608–1614, information technology's hard to imagine how the conservative religious community of Toledo would have understood its anguished gray sky, its unorthodox use of scale and its transformation of holy figures into stark, twisting panes of colour. Y'all tin only conclude that El Greco knew his audience was not simply the folks in boondocks, but past masters, futurity admirers and probably divine observers too.

El Greco was not a solitary wolf or a hermit. He was a shrewd businessman and he had supporters, though nil on the level of such hustling artist-politicians equally Titian or Rubens. After his death in 1614, however, at the dawning of the Baroque era, El Greco fell from favour. His idiosyncratic, sometimes agonizing style, with its bold rejection of naturalism – the very thing that makes him seem then fresh today – marked him in the 17th and 18th centuries as at best a minor painter on an off-ramp of art history, and at worst a madman. But El Greco wasn't mad at all. He was unmarried-minded, extravagant, stubborn perhaps and willing to expect for fame: for centuries, if needed

Rescued from history

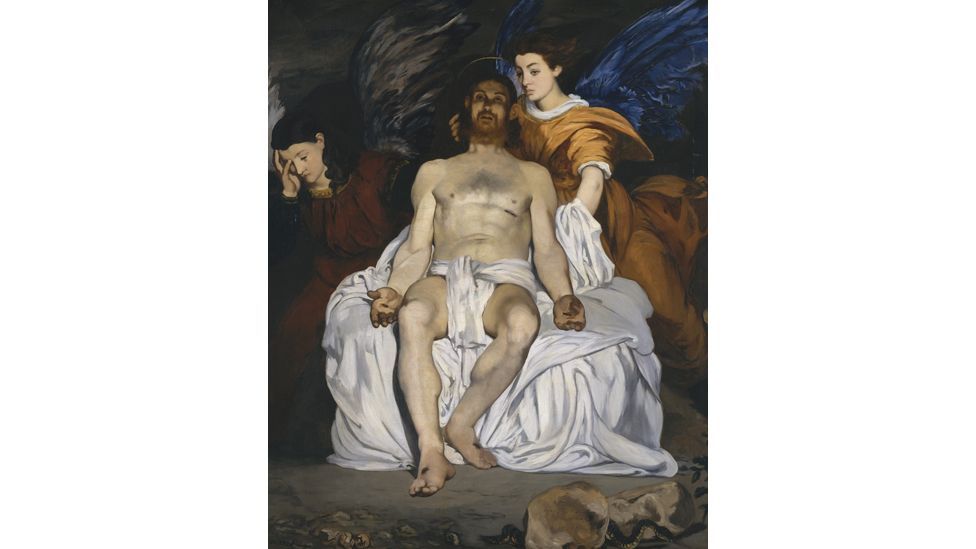

El Greco's revival began, like mod fine art itself, in Paris in the 19th Century. A new gallery of Spanish art at the Louvre – featuring nine El Grecos, plus a few that were misattributed – enraptured painters like Eugène Delacroix, who owned a copy of one of El Greco's scenes from the Passion. Édouard Manet, the human being with whom modern fine art truly begins, was a total Hispanophile, and in 1865 he traveled to Madrid and Toledo to meet El Greco's work up shut. Velázquez, Murillo and the other painters of Spain's Golden Historic period enraptured Manet, but he had to work difficult to digest their exacting compositions into his ain apartment, blunt way. El Greco hit closer to home. Manet'southward Dead Christ with Angels, now on loan to the Prado from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is deeply indebted to an El Greco annunciation from around 1600: in both, the affections swoops downwards from the right of the composition, blue-grayness wings splitting the sky.

The Dead Christ With Angels by Manet (Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, New York)

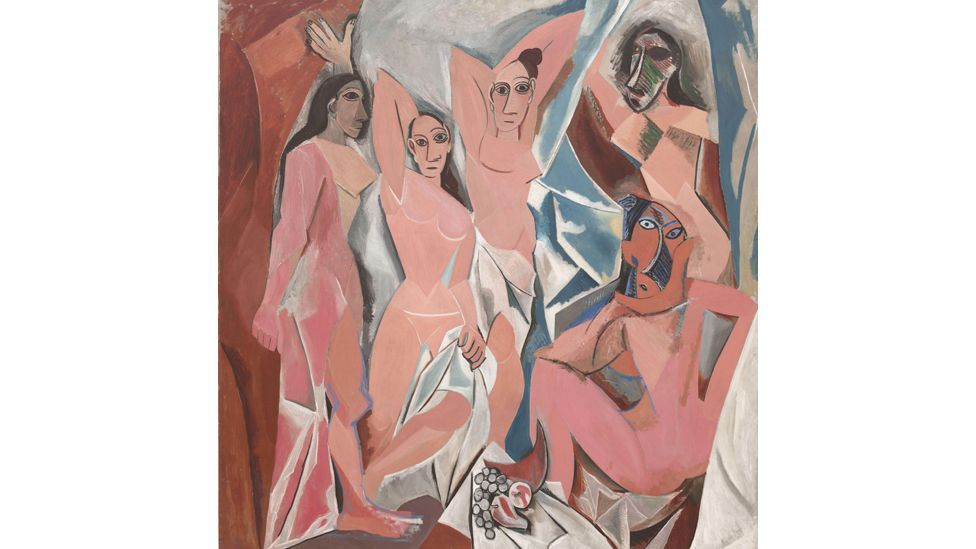

Paul Cézanne never fabricated information technology to Spain, but in 1885 he began copying an quondam portrait of a woman with a fur stole from a woodcut reproduction, one that was then credited to El Greco but is now in question. The copy is inappreciably Cézanne'south most interesting piece of work, but every bit he ventured further into the belittling way that would lay the foundations for abstraction, El Greco's influence endured: compare the older creative person's barren View of Toledo, with its radical articulation of space through color, to Cézanne's landscapes of Mont-Saint-Victoire. Even Cézanne's bathers, if you're feeling generous, seem to recall that Vision of Saint John from 3 centuries past – a painting that we know influenced Cézanne's biggest fan, Pablo Picasso, whose Demoiselles d'Avignon uses similar compositional logic. "Velázquez! What does everybody encounter in Velázquez these days?" Picasso once wailed. "I prefer El Greco a thousand times more. He was really a painter."

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon by Picasso (The Museum of Modern Fine art, New York)

Cézanne and Picasso's admiration did not account for the fact that El Greco was an extremely religious creative person, and that his deformations had a theological goal: in escaping from the exigencies of mimicry, he idea he could open a portal onto the divine. That was the appeal of El Greco for many German and Austrian artists of the turn of the 20th Century, among them Max Ernst, Franz Marc and Oskar Kokoschka, who plant in El Greco a paradigm for their expressionist paintings, which freighted landscapes and portraits with emotion. Even Jackson Pollock, not the first creative person you might name as a disciple of the Old Masters, learned something from his Greek-Spanish precursor. His sketchbooks are filled with more than two dozen drawings after El Greco, translating his Vision of Saint John into the combustible forms that would inform his early paintings, and lead eventually to his drips.

Information technology's easy to say that El Greco was 'ahead of his time', a modern artist born too soon. But in their recent, groundbreaking book Anachronic Renaissance, the art historians Alexander Nagel and Christopher Wood testify that art has never been locked down to a single spot on a timeline, but rather constantly oscillates betwixt by and hereafter, and even between temporality and eternity. A painting from the 16th Century has something to say about its historical moment, yep. Merely information technology is as well imbued with the art of the by, reactivated by viewers in the futurity and – as was widely believed and then – invested with a jiff of divinity that stands outside time itself. "The piece of work of art", write Nagel and Wood, "is a bulletin whose sender and destination are constantly shifting." Few artists prove that equally solidly as El Greco, an creative person in time and out of sync at once.

If you would like to annotate on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, caput over to our Facebook folio or message united states on Twitter .

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20140826-the-time-travelling-painter

0 Response to "What Are Some Cultured Mastered the Art of Narrative Painting"

Post a Comment